Jesús González Requena

Seminario Psicoanálisis y Análisis Textual 2007/2008

sesión del 23/05/2008 (2)

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

de esta edición: gonzalezrequena.com, 2015

- Brief Career As A Musical Prodigy

- Una mujer absolutamente inalcanzable y absolutamente insatisfecha

- La primera escena de suicidio

- Una mujer absolutamente inalcanzable y absolutamente insatisfecha

Brief Career As A Musical Prodigy

Orson Welles: Brief Career As A Musical Prodigy, Paris Vogue, No. 632, Dec. 1982 – Jan. 1983:

«Violonist, pianist … child conductor …

«This last was pretty much of a fake. By the time I was seven I was reading through the scores and waving my little baton in the presence of such people as Heifetz, Casals, Schnabel, Wallenstein and Mischa Ellman, when they gathered informally in chamber groups in my mother’s house. Her own professional life was frustrated by long illness, but just about everybody was in love with her, so the celebrated musicians, when they came to visit and play, were kind enough to pretend that the midget Von Karajan in front of them was not (as I must truly have been) a damned nuisance.

«I find it strange that my mother indulged me in this since she indulged in nothing else. She was not the musical version of a stage mother, but waas simply resolved that whatever I did had to be good if it was to be done at all, and I was made to practice hours on end every day.

«Once, distracted to the point of madness by endlessly repeated musical scales, I attempted suicide.

«What I really wanted to end, of course, was not my life but the scales, and I did place myself in a position of imminent peril on the outside of one of those railings in the Ritz some two and a half stories above the Place Vendome. I hung there listening to the wretched spinster lady who’d been engaged to supervise my practice calling hysterically for my mother in an adjoining room.

«Pause … Then my mother’s voice:

««”Well”, she said, “if he wants to jump, let him jump.”

«The truth is her heart was in her mouth. She knew her son, and knew that stepping off into space would have appealed to me for its gaudy element of melodrama and pathos. (“Now they’ll be sorry.”) She also imagined that a child could have no significant sense of the reality of death.

«But in this she was mistaken. I knew very well that she was going to die, and how real that would be, and how very soon it would happen. Whenever she left me, the moment the door had closed, I would burst into tears, afraid that I would never see her again.

«But she was certainly right about that business of mine out on the balcony. If I’d heard her rushing toward me the excitement might well have been just enough, and I wouldn’t be here now remembering it.

«Later, my mother told me that she stood still all that time in the hall outside the room with the piano. By the sheer force of her formidable character she persuaded the spinster lady to muffle her whimpering… Then, finally, there came to her ears the sound she’d been waiting for:

«”Do-re-mi-fa-sol…”

«My mother had won. She was, in all things, as tough-minded as she was loving-hearted.

«The last time I was allowed to visit her…

«It must have cost great effort and much pain to have let me find her sitting up in bed. And how much like her it was to have arranged it so that our farewell in that black room was made to seem like the high point of my birthday party.

«I heard that cello voice: “Well, now, Georgie-Porgie…”

«I’d just learned that I’d been baptized “George” -that “Orson was a mere middle name, and had reacted tragically to the revelation.

«My father had said, “Hell, we had to call you ‘Orson’ – every damned pullman porter in the country in named ‘George’.”

«My gangsterish little friends in the neighborhood had taken up the maddening chant:

«”Georgie-Porgie, puddin’ and pie,

«Kissed the girls and made them cry!”

«The first line of the hateful couplet seemed to sum up the chubbly chubby little grub larva I knew myself to be, but I rather liked the part about kissing

«Mother, who knew about that awful jingle, was teasing me – as she so often liked to do.

«Then I heard her again, a voice in the shadows, speaking Shakespeare:

«”These antique fables apprehend,

«More than cool reason ever comprehends.”

«The quotation – spoken, consolingly, came from her choice of a primer when she was first teaching me to read. “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” is not the easiest way to start spelling out one’s first written words, but “Why,” she demanded, “should a person at his most impressionable age be shovelled into the sordid company of ‘Auntie’s Nice Kitty-Cat,’ and ‘Little Sister’s Silly Red Ball’?”

«I was marinated in poetry, and to learn right at the beginning, “a sense of awe, delight and wonder.”

«And now she was holding me in one of her looks. Some of these could be quite terrible. I’d seen my father wither under them into a crisp, brown winter’s leaf.

«”The lunatic, the lover, and the poet

«Are of imagination all compact.”

«Those great shining eyes looked dark by the light of the eight small candles. I can remember now what I was thinking. I thought how green those eyes had always been when it was sunny.

«Then – all tenderness, as if speaking from an immense distance:

«”A lovely boy, stol’n from an Indian king,

«Who ever had so sweet a changeling…?”

«What did she mean? Was I, indeed, a changeling? (I have, in later years, been given certain hints…)

«Mother had told me that because it was just six o’clock in the morning: time for everyone to start to work in the factories, whistles and bells had all starded blowing at once, like heralds, at the moment of my birth.

«”That stupid birthday cake,” she said, “is just another stupid cake; and you’ll have all the cakes you want. But the candles are a fairy ring. And you will never again in your whole life have just that number to blow out.”

«She was a sorceress.

«”You must puff hard,” she said, “and you must blow out every one of them. And you must make a wish.”

«I puffed very hard. And suddenly the room was dark and my mother had vanished forever.

«Sometimes, in the dead watches of night, it strikes me that of all my mistakes, the greatest was on that birthday just before my mother died, when I forgot to make a wish.»

Una mujer absolutamente inalcanzable y absolutamente insatisfecha

Lo que nos conduce, necesariamente, aquí:

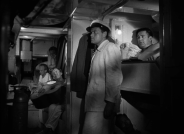

Anochece. En ausencia de la menor brisa, el barco se halla detenido en mar abierto.

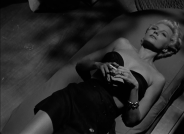

En el centro absoluto de la cubierta, del todo confundida con el espacio escénico, se encuentra Elsa, a la vez elevada y yaciente, absolutamente visible y absolutamente intocable.

Bannister: Michael.

Michael: Yes, sir.

¿No les parece que podría estar muerta?

Y literalmente a sus pies, por debajo del nivel que sus espléndidas piernas definen, los tres personajes masculinos.

Bannister: Michael, Mr. Grisby has told me something I’m very sorry to hear.

George toca el piano y marca la letra.

Elsa: “But if you kiss me”

Bannister: Lover, this really concerns you more than anyone else.

Y ella, ¿no es como si estuviera muerta?

Grisby: “Don’t take your arms away”

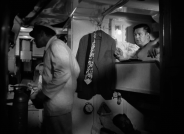

¿Por qué si Georges suda tan ostensiblemente

Michael no suda en absoluto?

Parece mortalmente pálido.

Bannister: According to George here, Michael is anxious to quit.

«Welles: For thirty years people have been asking me how I reconcile X with Y! The truthful answer is that I don’t. Everything about me is a contradiction, and so is everything about everybody else. We are made out of oppositions; we live between two poles. There’s a philistine and an aesthete in all of us, and a murderer and a saint. You don’t reconcile the poles. You just recognise them.»

[Kenneth Tynan, The World of Orson Welles, 1967]

Welles, gracias al trabajo artístico, pudo dar salida a las dos formas extremas que nacían de la escisión radical que lo atravesaba.

Y de hecho, cuando comparte plano con George, también Michael suda intensamente.

Bannister: Did you know about that, Lover?

La que no suda nada en absoluto es ella.

Elsa: No, I didn’t.

Bannister: Shut up, George.

¿Y por qué Michael a veces suda y a veces no?

¿Fallo de raccord?

Bannister: What’s the matter, hours too long?

Tiene lugar entonces, en el diálogo, una referencia casi directa a La vuelta al mundo en 80 días:

Michael: No, sir.

Bannister: How about the money?

Michael: I don’t care about that.

Bannister: So money doesn’t interest you, Michael? Are you independently wealthy?

Michael: I’m independent.

Bannister: Of money? Before you write that novel, you’d better learn something.

Bannister: You’ve been travelling the world too much to find out about it.

Y especialmente a su protagonista, Phileas Fogg, ese gentleman que -como Orson Welles, ¿será por eso que no suda?- atraviesa el mundo a toda velocidad sin percibir nada de él.

Que nunca se acalora, que no suda en absoluto.

Quien sí suda, y a chorros, es, insistamos en ello, Grisby.

Grisby: That’s good, Arthur.

Habla entonces el poeta:

Michael: Well, sir… I’ve always found it very sanitary to be broke.

El cineasta aplaude la frase:

Grisby: That’s good, too, Arthur.

Y el productor impone orden:

Bannister: Shut up, George.

Y explica el valor del dinero.

Bannister: Money cannot bring you health and happiness, etcetera. Is that it?

Bannister: Without money, I’d be flat on my back in the ward of a county hospital. Look at this yacht. It once belonged to Jules Bachrach.

El valor del dinero: esa era la obsesión mayor del padre de Welles, quien se desinteresaba por los valores artísticos a los que su esposa concedía la mayor importancia.

Bannister: The great Bachrach, who kept me out of his club because my mother was a Manchester Greek.

Desde luego, sin el dinero de la Columbia que Larry Cohn administraba, no hubiera sido posible alquilar a Errol Flynn el suntuoso yate en el que no sólo se rodó el film en el golfo de México, sino también en el que, con la compañía del propio Errol Flyn, se celebraron esas suntuosas fiestas durante el rodaje de las que ya les hablé en alguna ocasión.

Bannister: I got him on perjury.

¿Y este extraordinario plano, todo él lleno por la cara bañada de sudor de Grisby?

¿Tendrá algo que ver con ese perjurio del que se habla? Y ya saben que el perjurio consiste en jurar en falso, que es lo que había hecho Welles, también él artista, como el tal Bacharach, con respecto a la promesa hecha al padre poco antes de su muerte.

Bannister: He died bankrupt. And here I am.

A estas alturas resulta imposible atribuir ese contraste relativo a la presencia y la ausencia del sudor a un fallo de raccord.

Evidentemente se trata de otra pincelada de esa disociación radical que es la que opone a Michael y Grisby.

Como si uno fuera el adulto que entendiera todo lo que se dice y el otro fuera el niño, el marinerito, que no entendiera nada.

Y bien, en un momento dado, ella, la estrella, el cadáver resplandeciente, pide fuego, pues tiene en la mano ese cigarrillo sin encender que recorre toda la película:

Elsa: George.

I heard that cello voice: “Well, now, Georgie-Porgie…”

Deberían leer Georgie Porgie, ese relato breve de Kipling que, sorprendentemente, cuenta una historia muy parecida a la de Madame Butterflay.

Bannister: Each man has his own idea of happiness, of course.

Grisby: I haven’t matches.

Bannister: But money is what all of us have in common.

George dice que no tiene cerillas.

Y los dos rostros del film en los que se despliega Welles comparecen literalmente a los pies de la diosa.

En un momento en el que de lo que se trata puede ser de encender su cigarrillo tanto como de apagar las velas de la tarta del cumpleaños de la última despedida.

Bannister: Take Bessie here. She used to work for Bachrach. I pay her more, don’t I, Bessie?

Bessie: Yes, Mr. Bannister.

Bannister: Her salary means happiness. It means a home three rooms for two families. Bessie’s a grandmother, a widow. Only one of the boys works. Right, Bessie?

Bessie: Yes, sir.

Bannister: Yes, of course it is.

El subrayado sometimiento servil de Bessie ante Bannister encuentra su réplica, en imagen, en el equivalente del poeta hacia la estrella a través del cineasta.

Bannister: So Bessie goes to church every Sunday she gets off…

Bannister: and prays to God she’ll never be too old to earn the salary I pay her.

Y de la importancia de esta tortuosa circulación del fuego y del cigarrillo es testigo el insólito punto de vista cenital que se introduce entonces:

Un punto de vista cenital que nos muestra a una mujer absolutamente inalcanzable y absolutamente insatisfecha.

Bannister: Sing it for us again, Lover.

Michael: Why do you stand for that, Bessie? I’m quitting. Why don’t you?

Bessie: You heard him, Mr. Poet.

«The lunatic, the lover, and the poet

«Are of imagination all compact.”

Y así empezamos a percibir presentes en la escena todos los elementos de esa otra escena que fue la de la muerte de la madre.

Bessie: I need the money.

Michael: Talk of money and murder. I must be insane.

Michael: Or else all these people are lunatics.

«”The lunatic, the lover, and the poet

Are of imagination all compact.»

Bessie: That’s why I can’t leave. That poor little child he married.

Bessie: Somebody’s got to take care of her.

Elsa: “Don’t hold me

Elsa: “But if you hold me

Elsa: “Don’t take your arms away

Elsa: “Comes a change of heart

Elsa: “Please don’t love me

«The lunatic, the lover, and the poet

«Are of imagination all compact.»

Elsa: “But, if you love me

Elsa: “Then don’t take your lips

Elsa: “Or your arms, or your love

Podría ser una despedida definitiva.

Pero podría ser igualmente, un abrazo definitivo.

Elsa: “away”

Son estos términos contradictorios, desde luego, pero no lo son menos los de la letra de la canción:

Elsa: “Don’t hold me But if you hold me Don’t take your arms away

«She was a sorceress.»

¿Cómo prefieren traducirlo?

¿Como hechicera o como bruja? En cualquier caso sus poderes hipnotizan a toda la tripulación del barco.

Elsa: Comes a change in weather,

Se habla del tiempo, pues se habla del paso del tiempo, del cambio de los sentimientos.

Elsa: “Comes a change of heart

Elsa: “And who knows when the rain Will start?

De las lágrimas.

Y se retorna al enunciado contradictorio, que finalmente devuelve la lógica extrema de la nada o del todo.

Elsa: “Please don’t love me

Elsa: “But, if you love me

Elsa: “Then don’t take your lips

Elsa: “Or your arms, or your love

¿Como podría evitarse la sensación de que ella está muriendo ahora?

Elsa: “away”

Es decir, que está muriendo siempre, pues la escena permanece siempre inconclusa en el relato que de que ella nos ofreció Welles:

«That stupid birthday cake,” she said, “is just another stupid cake; and you’ll have all the cakes you want. But the candles are a fairy ring. And you will never again in your whole life have just that number to blow out.

«She was a sorceress.

«You must puff hard,” she said, “and you must blow out every one of them. And you must make a wish.

«I puffed very hard. And suddenly the room was dark and my mother had vanished forever.

«Sometimes, in the dead watches of night, it strikes me that of all my mistakes, the greatest was on that birthday just before my mother died, when I forgot to make a wish.»

¿Llegó a haber abrazo en aquella despedida entre la madre y el hijo?

Todo parece indicar que no: Sometimes, in the dead watches of night, it strikes me that of all my mistakes, the greatest was on that birthday just before my mother died, when I forgot to make a wish.

Pues todo parece indicar que el cineasta siguió siempre, en sus noches desveladas, arrepintiéndose de no haber sido capaz de pensar un deseo.

Aunque esta vez conviene incurrir en un anglicismo en la traducción y decir: hacer un deseo, pues de eso precisamente se trata.

Quizás nos encontremos ante el núcleo del eterno insomnio wellesiano.

Todo parece indicar, por tanto, que no llego a haber abrazo.

Es más, en cierto modo, eso está escrito ahí: I puffed very hard. And suddenly the room was dark and my mother had vanished forever.

El sopló sin haber llegado a hacer un deseo y de pronto la habitación se oscureció y mi madre desapareció para siempre.

Elsa: “But, if you love me

Elsa: “Then don’t take your lips

Elsa: “Or your arms, or your love

Elsa: “away”

«That stupid birthday cake,” she said, “is just another stupid cake; and you’ll have all the cakes you want. But the candles are a fairy ring. And you will never again in your whole life have just that number to blow out.»

Me decía, cuando trabajaba en esta secuencia, que era una pena que la palabra inglesa candle no tuviera el doble sentido de la palabra española vela, que nombra a la vez las velas del velero (sail) y las velas que alumbran (candle).

Pues en tal caso las velas de la escena, esas velas de cumpleaños que cubren la tarta, hubieran encontrado su expresión a través de las velas del velero.

Claro está, no es así, el inglés no lo permite. Y sin embargo…

Sin embargo, dándole vueltas a la cuestión comprendí porque Michael O’Hara es marinero. Pues el marinero es un sailor. Es decir, un hombre de velas. Y las velas permiten navegar cuando el viento sopla sobre ellas.

De modo que un marinero es alguien todo él entregado a ese soplido, aun cuando él mismo, sin embargo, no pueda provocarlo.

Y ni que decir tiene, esta escena tiene lugar en un calmo atardecer caribeño en el que no sopla el más mínimo viento.

Para que el viento sople y haga navegar la embarcación hace falta que un dios lo ordene, nada puede hacer en eso un simple marinero. Y mucho menos un marinerito que se sabe visto como un estúpido y al que sin embargo se le exige que sea un genio.

¿Qué por qué digo que se sabe visto como un estúpido?

Porque así se lo dice su madre, una y otra vez:

«That stupid birthday cake,” she said, “is just another stupid cake; and you’ll have all the cakes you want. But the candles are a fairy ring. And you will never again in your whole life have just that number to blow out.”

Esa estúpida tarta de cumpleaños –That stupid birthday cake- es, para su madre, él mismo: Georgie-Porgie, puddin’ and pie, Kissed the girls and made them cry!”

«The first line of the hateful couplet seemed to sum up the chubbly chubby little grub larva I knew myself to be, but I rather liked the part about kissing girls.

«Mother, who knew about that awful jingle, was teasing me – as she so often liked to do.

La primera escena de suicidio

¿Cómo no acordarse entonces de ese primer intento de suicidio del marinerito Welles, cuando intentaba huir a la desesperada de la exigencia materna de que de él, no más que un estúpido Georgie-Porkie, saliera nada menos que un niño prodigio de la música?

«Once, distracted to the point of madness by endlessly repeated musical scales, I attempted suicide.

«What I really wanted to end, of course, was not my life but the scales, and I did place myself in a position of imminent peril on the outside of one of those railings in the Ritz some two and a half stories above the Place Vendome. I hung there listening to the wretched spinster lady who’d been engaged to supervise my practice calling hysterically for my mother in an adjoining room.

«Pause … Then my mother’s voice:

«”Well“, she said, “if he wants to jump, let him jump.”

«The truth is her heart was in her mouth. She knew her son, and knew that stepping off into space would have appealed to me for its gaudy element of melodrama and pathos. (“Now they’ll be sorry.”) She also imagined that a child could have no significant sense of the reality of death.

«But in this she was mistaken. I knew very well that she was going to die, and how real that would be, and how very soon it would happen. Whenever she left me, the moment the door had closed, I would burst into tears, afraid that I would never see her again. «But she was certainly right about that business of mine out on the balcony. If I’d heard her rushing toward me the excitement might well have been just enough, and I wouldn’t be here now remembering it.

«Later, my mother told me that she stood still all that time in the hall outside the room with the piano. By the sheer force of her formidable character she persuaded the spinster lady to muffle her whimpering… Then, finally, there came to her ears the sound she’d been waiting for:

«”Do-re-mi-fa-sol…”

«My mother had won. She was, in all things, as tough-minded as she was loving-hearted.»

Me contaba Ana María, en el correo en el que nos envió la traducción del texto que ustedes conocen, la extrema dificultad que le había supuesto la enrevesada escritura de Welles.

Tiene razón, desde luego, pero la tiene, especialmente, aquí.

Pues si recuerdan el texto, escrito simultáneamente, dedicado a la muerte del padre, recordarán también que era mucho más sencillo en su escritura, mucho más fácil de traducir.

Lo que indica que el carácter extraordinariamente enrevesado de la escritura de este texto -muy próxima en su enrevesamiento, dicho sea de paso, a la de los Escritos de Lacan- es en sí mismo revelador de la extraordinaria dificultad que hubo de suponer siempre para él su relación con su madre.

En su punto de partida hay una neta vivencia de enloquecimiento ante la demanda materna: distracted to the point of madness by endlessly repeated musical scales.

¿Y cómo no sentirnos impresionados ante el brutal enunciado materno que la ha generado? –Bien, si quiere saltar, que salte. –“Well“, she said, “if he wants to jump, let him jump.”

Es decir: si no es capaz de ser un genio, si sólo va a ser ese estúpido regordete de Georgie-Porgie, que salte y me deje en paz de una vez.

Y no menos terrible es la certidumbre de ambos de que la cosa iba en serio, de que se trataba de una auténtica tentativa de suicidio de ese niño que todavía no había cumplido los 9 años:

«She knew her son, and knew that stepping off into space would have appealed to me for its gaudy element of melodrama and pathos.

«she was certainly right about that business of mine out on the balcony. If I’d heard her rushing toward me the excitement might well have been just enough, and I wouldn’t be here now remembering it.

Y el reconocimiento de la pura fuerza de su formidable carácter que hacía de ella, siempre, una ganadora –By the sheer force of her formidable character.

Y la formulación final del doble vínculo con el que le atrapaba: ella, la ganadora, era tan dura en sus decisiones como tierna de corazón –My mother had won. She was, in all things, as tough-minded as she was loving-hearted.

Podríamos estar escuchando a ese señor de Winter que fue Alfred Hitchcock hablando de su madre bajo el nombre de Rebeca.

De modo que todo parece indicar que, uno como otro, las odiaban tan intensamente como las amaban, por más que no fueran capaces de confesarse a sí mismos ese odio.

Ahora bien, ¿por qué dice Welles que en esa tarta sólo había 8 velas si, cuando su madre murió él ya había cumplido los 9 años?

«”The lunatic, the lover, and the poet

«Are of imagination all compact.”

«Those great shining eyes looked dark by the light of the eight small candles. I can remember now what I was thinking. I thought how green those eyes had always been when it was sunny.

«Then – all tenderness, as if speaking from an immense distance:

«”A lovely boy, stol’n from an Indian king,

«Who ever had so sweet a changeling…?”

«What did she mean? Was I, indeed, a changeling? (I have, in later years, been given certain hints…)

««”That stupid birthday cake,” she said, “is just another stupid cake; and you’ll have all the cakes you want. But the candles are a fairy ring. And you will never again in your whole life have just that number to blow out.”

«She was a sorceress.”»

Como ven, hay en ello un motivo sobrado para leer La vuelta a mundo en 80 días.

Pues el 0 de 80, tanto como la propia vuelta al mundo, pueden ser círculos mágicos que nos expliquen el motivo que late en el insidioso deslizamiento de la palabra changeling ahí.